A Grim Fairy Tale

Imagination does wonders to reality. For kids, toys can come to life; pillows and blankets make fortresses; and imaginary friends provide constant company. As we get older, we lose a bit of the magic, but we can daydream of winning the lotto or telling off a coworker without getting fired. Imagination helps us cope with or escape from our current struggles. Even the monster under our bed is much less frightening than the skeletons we keep in our closets or freezers.

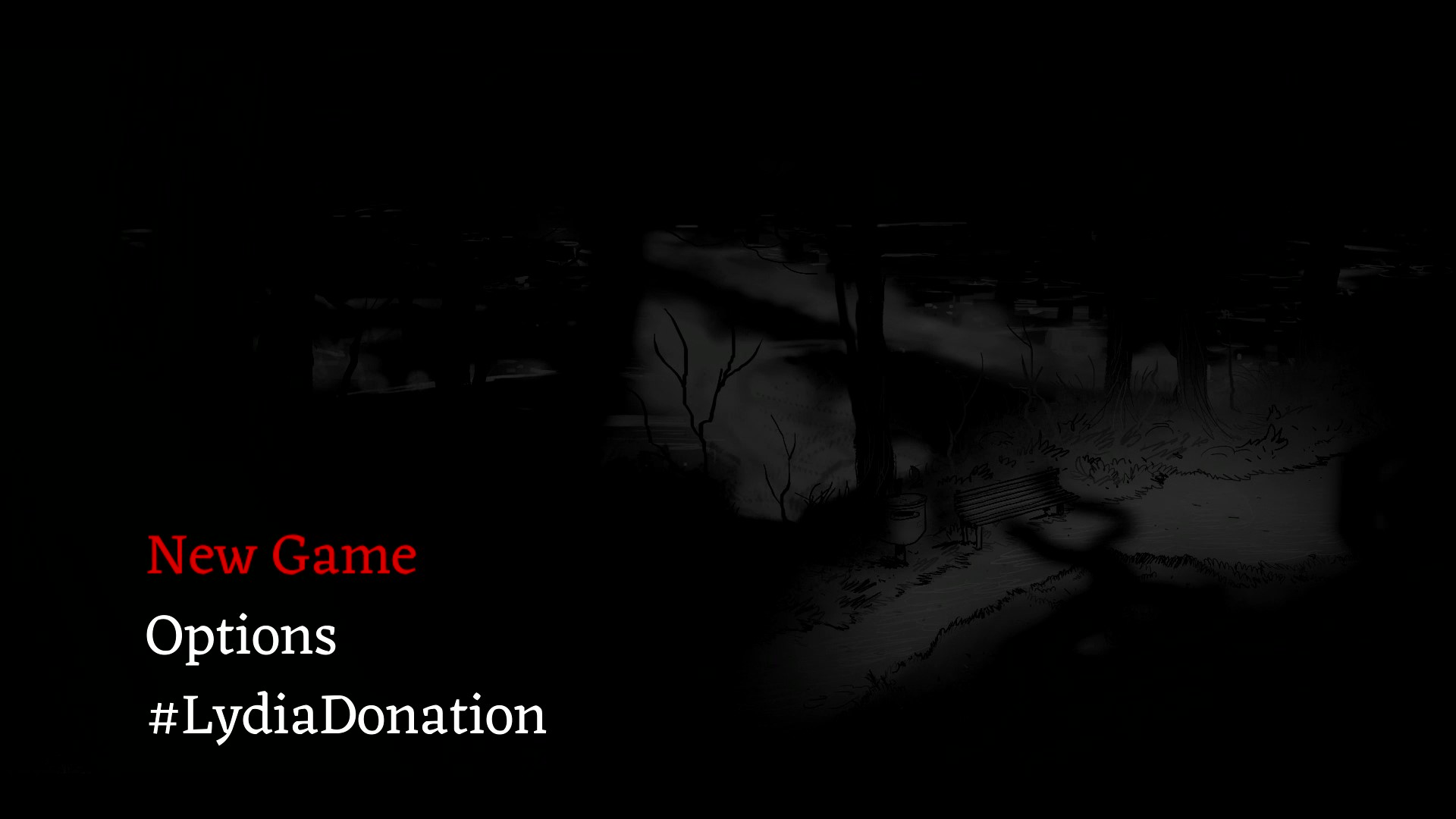

Unless we give into our delusions, imagination has its limits, and reality never leaves. Lydia plays with this concept, pitting a girl’s imagination and innocence against the trauma she experiences in the real world. Although video games act as a form of escapism in general, Lydia does not shy away from the harsh realities of substance abuse, parental neglect, and death. You’ll find fantastical elements throughout its short runtime, but they won’t soften the gut punch the game delivers, and that pain is welcome.

What is it?

Lydia plays as a series of vignettes about its titular character’s life, showing how her childhood is impacted by her parents’ substance use. Reality and fiction blend together as her pink bear, Teddy, comes to life and attempts to use her imagination to shield her from her distress. Considering this adventure will take you around an hour, detailing any more of the plot will spoil it. Suffice to say the developers aimed to make a “feel bad game,” so the story caters to those who enjoy monochrome rainbows and hornless unicorns.

Like the other mental health games I’ve reviewed, Lydia rarely ventures from its walking simulator roots. You will guide the girl between each scene and scroll through dialogue. Occasionally, you can choose what to say, and two set pieces almost play like a point-and-click adventure. The game ultimately wants to tell you a story, and your main responsibility is to listen, you petulant child.

What’s good?

- Fortunately, that story will keep you emotionally invested. Lydia nails a bleak tone without drowning you in sob stories, instilling the same sense of festering dread that its main character experiences. The story is a morbid train wreck of misery, and watching the destruction is as enlightening as it is sobering.

- The art direction manages to be unsettling without being overbearing. The scenes look like they’re taken from a children’s book, but the primary colors of this world are black, gray, and red. Characters jerk back and forth; shadows hide much of the environment, and a grainy film gives a sense of decay. The illustrations may recall childhood innocence, but the art serves as a constant reminder that things aren’t right.

What’s a double-edged sword?

You’ll finish the story in one hour or so. This allows you to enjoy the full game in one sitting, and you won’t be wading through any filler. Across its four chapters, Lydia clearly depicts how neglect can disrupt a child’s life, but it doesn’t dive into the characters, themselves. Given another thirty minutes or even an hour, the game could have presented a larger message on its themes.

What’s bad?

- Lydia’s fantasy scenes come off as more cliché than symbolic. Teddy represents innocence, but he functions like an ineffective Gemini Cricket who narrates what we already know. We see certain adults as monsters, but this association is so obvious that we don’t need this illustrated. The game’s most poignant scenes focus only on reality, such as one section which finds Lydia in a park. By focusing on the mundane, we see exactly how this girl survives. The fantasy is just fluff and almost feels like it was added to make the game easier for players to stomach.

- Your choices don’t matter. A walking simulator only benefits from player interaction when it actually impacts the gameplay. For Lydia, you can choose how the main character responds emotionally (with options like “Angry” or “Sad”), but you’ll only see a line or two of unique dialogue before its back to the script. When the choices are basically “Yes,” “Sure,” and “Righty-O, Daddy-O,” the game has incentivized button-mashing, not thoughtful story-telling.

What’s the verdict?

As the video game equivalent of flash fiction, Lydia delivers a poignant and profound story about distressing themes. It won’t make you feel good about yourself or humanity, but it will stick with you, make you think. Like many of its close cousins, Lydia struggles to be anything more than an interactive story, and given more meat, it could have done more with that story. Because of this, it’s not going to convert you to the genre, but if you do enjoy a dreary tale, Lydia is anti-soul food.

Arbitrary Statistics:

- Score: 7

- Time Played: Approximately one hour

- Number of Players: 1

- Games Like It on Switch: Soul Searching, Night in the Woods